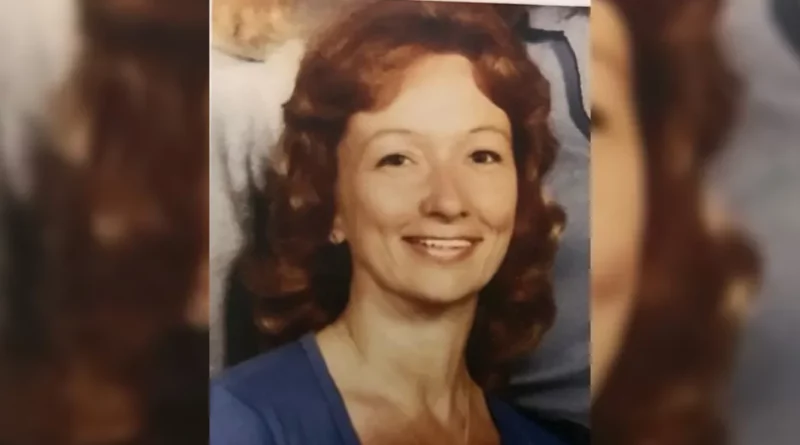

Yvonne Carol Menke 1985 Murder Has Been Resolved and 80 Year Old Woman Arrested for St. Croix Falls Wisconsin Killing

St. Croix Falls, Wisconsin, is the kind of place where the cold season arrives like a slow-moving curtain: first frost on the rooftops, a hush over the pines, and then, for months, the steady rhythm of winter. On the morning of December 12, 1985, that rhythm was broken. In the predawn dim, near an apartment building just a few blocks from the St. Croix River, 45-year-old Yvonne Carol Menke stepped out to begin another workday. She never made it. Within minutes, the sound of gunfire ricocheted off the buildings and into the alleyways. A neighbor, startled and then frightened, would soon glimpse a figure moving away. By the time first responders arrived, shock had already begun its slow climb through the community’s spine.

People in small towns like St. Croix Falls mark time by seasons, birthdays, and school calendars; by church potlucks and Friday night drives. After that morning, many residents learned to mark time by something else: before Yvonne’s killing, and after. An act of violence so intimate—delivered at the threshold of an ordinary day—settled over the town like hard frost.

Who Yvonne was, beyond the headlines

To understand the gravity of the crime, you have to understand Yvonne not as a name in a case file but as a whole person. She was a working woman, a mother, a friend known for a matter-of-fact kindness that made space for others. Co-workers recall that she didn’t advertise her troubles; she carried them privately, lightening the load for the people around her. She was the type who left notes on the fridge, reminders for herself and gentle nudges for her children. She cared about what the day’s work produced—not just for herself, but for the team.

Her life was not a headline. It was the layered story of a woman in her mid-forties, balancing responsibilities, relationships, hopes for the near future. She was old enough to have lived through hard lessons, young enough to still build new plans. On that morning in December, she did what millions do every day: stepped out her door, keys in hand, thinking more about the tasks ahead than the risk behind her.

The morning of the murder

Shortly after 6:00 a.m., the neighborhood wore the usual cloak of winter quiet. In the half-light, breath turned to vapor, windshields held a skin of ice, and a routine unfolded—lights flicked on, cars coughed to life. It was within this ordinary choreography that the shooting occurred. Yvonne was attacked at close range, shot multiple times, the violence deliberate and composed. A killer came prepared for proximity.

Witness accounts would later describe someone moving quickly away from the scene, bundled against the cold, disappearing into the pattern of alleys and side streets that cut the town into small squares. There were no smartphone cameras, no doorbell systems to stitch together the flight. What remained were human memories, fragments of description, and the physical traces pressed into snow and grit: footprints, tire impressions, and the chaos of motion frozen at the edge of a Wisconsin winter morning.

The first investigation: fragments and frustration

The initial investigation moved the way many homicide inquiries do in their first days: broad and urgent. Detectives canvassed apartments, collected statements, and tried to frame what happened inside a workable box of motive and means. Everyone knew that violent crimes in small towns are rarely random. Most begin at the frayed ends of relationships—love, jealousy, money, resentment—and then unravel into calamity.

What investigators could piece together suggested a targeted attack. Evidence pointed away from a robbery gone wrong and toward someone who knew Yvonne’s patterns—the time she left for work, the way she started her mornings. The killer either laid in wait or arrived just in time, knowing precisely when opportunity would appear.

But for all their effort, detectives soon confronted the cold facts of 1985 policing: limited forensic technology, slower data sharing, and the absence of modern databases that now easily connect small clues to bigger patterns. The case did not die, but it cooled. Tips slowed. Leads thinned. The file thickened—pages added, not because of breakthroughs, but because of time.

Rumors of motive: a triangle’s rough geometry

In most homicides, motive is the story you can tell even before you know all the details. Early whispers turned toward the jagged edges of a relationship triangle that had formed around Yvonne and another woman, with a man at the apex whose choices and affections bled into conflict. People close to the situation spoke of jealousy, of slights and suspicions, of the sharpened envy that grows when intimacy and insecurity share the same room.

Investigators, attuned to the social geometry of such cases, probed that triangle—who said what, who went where, who feared losing what they believed was theirs. A name surfaced more than once: Mary Josephine Bailey, then living near the community and entangled, by love and rivalry, in a situation that could ferment into violence. It was not proof, only a direction. In 1985, directions could be miles of road without a map.

What the crime scene still had to say

Even in an era before DNA dominated the narrative, scenes like this one spoke in the quiet language of trace and impression. Footwear impressions—one boot in particular—etched a repeating pattern investigators believed was significant. There were fibers and the arrangement of shell casings; the geometry of wounds could suggest distance and stance. Sometimes the smallest oddity in a victim’s belongings—an unexpected scrap of paper, a note with a name or a number, a car detail—can later become a lighthouse for a cold case detective.

Across weeks and months, the practical craft of homicide work—interview, document, compare, re-interview—built the scaffolding of a theory: a targeted ambush, likely motivated by jealousy, executed by someone who knew the victim’s morning ritual. It was persuasive but incomplete, a near-story missing one or two sentences that only physical evidence or a confession could finally supply. Those sentences refused to appear.

The long freeze: years of unanswered questions

Cold cases are not static; they are elastic. They stretch across decades, adhering to the memory of a family, a street, a town. Children become adults who still speak of the wound. Detectives retire and others inherit the file, adding notes in different handwriting, drawing fresh diagrams over the old. The crime does not disappear; it waits.

For Yvonne’s loved ones, the waiting reshaped daily life. Anniversaries are not celebrations when a life was stolen on that date. Holidays carry a seat that is forever empty. Even the ordinary becomes charged: a winter morning looks like that winter morning, a set of footsteps in snow sounds like the ones that fled after the gunshots. This is what violence does—it stops one life and complicates many.

Cold case work evolves—and the file warms

Decades later, a new generation of investigators revisited the Menke homicide with patience and better tools. Cold case units often begin by re-reading every page, then building a new timeline one hour at a time. They re-interview witnesses who were once too scared or too uncertain, and who now, with the benefit of time and distance, can say a little more. They also apply modern forensics to old evidence: enhanced imaging for footwear impressions, computerized databases for pattern matching, and refined techniques for tracing the provenance of items that once seemed mundane.

In the Menke file, detail after detail—some small, some stubbornly persistent—began to align with the theory investigators had long suspected. The triangle of motive sharpened. The path toward a suspect, once hazy, gained edges. What a detective needs most in a cold case is a critical mass of converging facts—each independently fragile, but together sturdy enough to hold the weight of a charge.

The arrest at 80: a knock on a very old door

In November 2023, after nearly four decades of drift and duty, law enforcement officers traveled far from the winter alleys of St. Croix Falls to a home in Arizona. There, they arrested Mary Josephine Bailey, now 80 years old, on a charge of first-degree murder in Yvonne Menke’s killing.

An arrest that distant from the event is never simple. It requires not only new analysis but also the courage to trust the integrity of an old case file, to stand up in court and say: the story the evidence told us in 1985 is the same story it tells in 2023, and now we can prove it. The public often reacts to an elderly suspect with cognitive dissonance—how could someone who uses a cane and speaks softly have once pulled a trigger? But age softens a person’s posture, not the moral gravity of their choices.

The arrest was more than a procedural milestone. For Yvonne’s family, it reshaped the narrative they had been forced to tell themselves for decades. Where there had been a period at the end of an unfinished sentence, there was now a comma—followed by a courtroom.

From allegation to adjudication: the courtroom’s hard light

The prosecution of a cold case is an exercise in narrative control and forensic patience. Prosecutors must present a mosaic: each piece on its own seems insufficient, but in total, the picture resolves. They rely on physical traces that survived, on contemporaneous notes that freeze a memory in ink, on witnesses who—though older—can still summon the image of a winter morning and what they saw or heard.

In the case against Mary Josephine Bailey, the state’s theory hewed to the timeline built in 1985: jealousy born of a tangled relationship, planning carried out during pre-work hours, and an ambush at the edge of a daybreak routine. The defense, as is their duty, pressed the frailties—memories fade; people misremember; snow changes impressions; the lack of instant forensic miracles in 1985 left gaps one could drive a reasonable doubt through.

Jurors in cases like this learn to live inside nuance. The law does not demand certainty; it demands proof beyond a reasonable doubt. That is a human standard—weighty, but not mathematical. The question becomes whether the overall shape of the case leaves room for any reasonable alternative story.

Evidence under the microscope

Items that once seemed understated became central. Footwear impressions that matched a style linked to the accused. The timing of movements that morning; who was where and when. Notes and vehicle details that tied lives together more tightly than anyone wanted to admit. Old interviews, re-examined, placed the suspect near key locations at key times.

Even without the dramatic flourish of DNA, the physical universe of the scene remained stubborn: bullets travel along physics, shoes compress snow with consistent geometry, and paper either exists in a purse or it doesn’t. Prosecutors asked the jury to look at the cumulative weight, not the flash. Cold cases are rarely won with a single thunderclap; they are won by the steady accumulation of rain.

A verdict nearly 40 years in the making

When the jury returned its verdict, it did so against a backdrop of almost four decades of waiting. The finding of guilt spoke not only to the evidence but to the belief that time, while it erodes some things, can also clarify. Accountability does not spoil. Courts are not designed to heal grief; they are designed to adjudicate responsibility. Still, in that courtroom, the verdict carried a human vibration—Yvonne’s children and friends hearing, at last, that the system recognized what they had lived with all along.

Sentencing and the peculiarities of time

Because the crime occurred in 1985, the sentencing framework followed the law as it existed then. That matters. Statutes change; parole eligibility shifts with legislative winds. Here, the law’s vintage created a paradox of time: an elderly defendant receiving a life sentence that includes a theoretical path to parole years down the line—a possibility that, given age alone, is more arithmetic than hope.

The judge’s words acknowledged the strange geometry: the court exists in the present, applying the law of the past, to deliver a verdict that will reverberate into the future. The sentence underscored the central truth that violence compresses and distends time. For the victim’s family, the space between 1985 and today is not measured in calendar pages; it is measured in missed birthdays, unmade calls, and the quiet ache of normal days without someone you love.

Why an 80-year-old arrest matters

Some ask: what is gained by arresting and prosecuting someone so late in life for a crime so long ago? The answer is layered. First, justice is not a fruit with a short shelf life; its value does not diminish because years have passed. Second, the community deserves a formal accounting—a record that says, “This happened here, and we did not forget.” Third, cold case work advances only if it proves, in real courtrooms, that carefully tended facts can still yield accountability.

There is also a quiet, personal rationale. The families of victims carry a kind of secondhand sentence: the suspicion that the world is indifferent to their loss. A late arrest tells them that someone still cared enough to knock on doors, re-bag evidence, and read old reports until the ink smudged. That matters.

The anatomy of jealousy and escalation

Criminology has long mapped the pipeline from jealousy to violence. Intimate partner contexts—romantic rivalries, love triangles, perceived slights—can be among the most volatile. When jealousy fuses with opportunity and a perceived slight to one’s status or belonging, it can incubate a plan. That plan doesn’t require sophistication. It requires proximity, timing, and a willingness to cross a moral Rubicon at the exact moment another person is most vulnerable—like a winter morning, before sunrise, with keys in hand and the car door half-open.

The Menke case is an austere demonstration of that escalation. The motive is not exotic. It is painfully ordinary: fear of losing a relationship, anger that someone else might “win,” the corrosive need to reassert control. These are the combustible materials of many homicides.

The role of persistence: detectives as caretakers of memory

Cold case detectives often describe their work as custodial. They keep a case alive by tending to its memory. In practical terms, that means audits of evidence rooms, re-packaging and testing items with new methods, revisiting scenes, and monitoring witnesses whose circumstances change. Someone who was unwilling to talk in 1985 might be ready in 2015; relationships shift; loyalties bend; conscience grows louder.

What cracked the Menke case open was not one miracle; it was a chorus of small songs: a footwear pattern re-considered, an old note re-weighted, witness recollections re-contextualized, a timeline made precise by cross-checking the ordinary—work schedules, vehicle records, and the way a winter day in a small town begins.

Living with the verdict: the family’s long arc

For Yvonne’s family, the aftermath of a conviction is not an ending so much as a reorientation. The past becomes more legible: the questions that once spiraled now have edges; the what-ifs shrink, even if they never vanish. Grief, however, is not erased by clarity. For many survivors, the day of sentencing is followed by the first day of a new kind of quiet. The courtroom closes, the cameras leave, and you are left with a different kind of silence—the one in which you learn how to carry the truth and continue.

Yet there is, often, a crease of relief. Not joy—relief. The kind that lets you breathe more fully, because the story your family has told around kitchen tables for decades finally has a public counterpart. The community can say Yvonne’s name and fix it to a resolved narrative, not just a question.

The community’s memory and the town’s promise

St. Croix Falls is not defined by a single winter morning; it is defined by all the mornings before and after—by the river that carves the border, by the storefronts that unlock at dawn, by neighbors who still wave from their porches even when the air bites. But communities also keep ledgers of what happened on their streets. This case now sits in the ledger as an entry with a conclusion.

Cold cases solved in small towns become part of their civics lessons: a reminder that even when it appears nothing is happening, someone is working the night shift of justice. It strengthens civic trust and signals to would-be offenders that the passage of time is not a sanctuary.

Lessons for the craft of justice

The Menke case offers a blueprint for investigators and prosecutors everywhere:

- Return to the file. Treat old notes as living documents.

- Rebuild the timeline. A minute-by-minute reconstruction often exposes the single contradiction that matters.

- Re-interview. Time changes what people remember and what they are willing to say.

- Re-weight evidence. What seemed minor once might prove pivotal under modern scrutiny.

- Tell a coherent story. Jurors decide cases when the cumulative facts leave no reasonable room for another narrative.

These are not glamorous steps, but they are the backbone of cold case accountability. The victory lap in a courtroom is paved with a thousand quiet decisions in evidence rooms and interview cubicles.

The human center: saying Yvonne’s name

Criminal cases so often become dominated by the defendant’s biography—age, health, the shock of seeing a grandmotherly figure in a mugshot—that the victim can recede from view. It is important to say her name: Yvonne Carol Menke. She was a daughter, a mother, a colleague, and a person whose ordinary morning was stolen. Justice, late or not, is measured in whether our systems can still speak for those who no longer can.

When we tell this story to future generations, the point is not that an elderly person went to prison. The point is that a woman’s life mattered enough for a town and a justice system to refuse forgetting. The point is that love’s dark twin—jealousy—can be recognized, named, and interrupted before it becomes violence. The point is that the past is not beyond reach.

Afterword: what accountability does—and does not—do

Accountability cannot restore a life. It cannot give a family back the everyday, which is the deepest currency of love. What it can do is anchor the truth. It can show that the arc of a case, even stretched and warped by time, can still land in a courtroom and say, “This is what happened, and this is who did it.”

In that sense, the Menke case is both singular and instructive. Singular, because every victim’s story is irreplaceable. Instructive, because it demonstrates that time is not merely an enemy of prosecution; with care, it can be an ally—setting the stage for witnesses to speak, for science to advance, and for courage to mature in those tasked with carrying a file across decades.

The legacy of a winter morning

On future December mornings in St. Croix Falls, winds will still comb the trees and frost will still silver the town. Cars will still cough awake before sunrise. Somewhere, someone will think of Yvonne. Someone will glance at a stairwell, a parking spot, a slice of alley, and remember that violence once walked here, and that justice, though late, followed.

And if there is a final lesson, it is this: a community’s memory is a form of protection. When we keep faith with those we’ve lost, we also keep faith with the living.

Discover more from City Towner

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.