Jodine Serrin Killed in Her Bedroom by Unidentified Man in Carlsbad California

On February 14, 2007—Valentine’s Day—the quiet coastal city of Carlsbad, California, confronted a crime that would haunt investigators and the community for more than a decade: the murder of 39-year-old Jodine Elizabeth Serrin inside her own condominium. What began as a welfare check by devoted parents transformed into a complex homicide investigation, a long cold case, and ultimately a DNA-driven identification of a deceased suspect. This article reconstructs the known facts of Jodine’s life and final day, the immediate response, the evidence trail, the long period of investigative stagnation, the technological breakthroughs that reignited the case, and the broader lessons it teaches about modern forensic work, victim dignity, and community resilience.

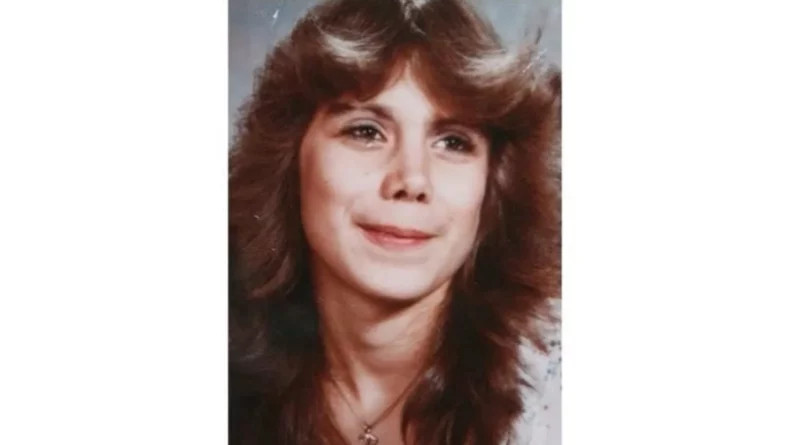

Who Was Jodine Elizabeth Serrin

Jodine, known to friends and family as warm, routine-oriented, and unfailingly kind, was a highly functioning woman living with developmental disabilities. She worked, managed her day-to-day life with a cherished sense of independence, and maintained a close relationship with her parents, who supported that independence while checking in regularly. Jodine thrived on predictability—appointments kept, calls returned, doors locked at night—and she was active in local social and support groups that offered community and structure.

Friends described her as earnest and trusting, someone who took people at face value. She loved books and television dramas, she was meticulous about keeping her living space tidy, and she followed a schedule that brought her comfort. That same predictability gave those who loved her a keen sense of when something felt off. It also gave investigators, later, an unusually clear baseline for noticing the slightest deviation in her movements and communications around the day of her death.

The Setting: Carlsbad, California, and the 1900 Block of Swallow Lane

Carlsbad in 2007 was a rapidly growing North County San Diego community known for its beaches, flower fields, and quiet, master-planned neighborhoods. The 1900 block of Swallow Lane sits in a residential area made up of modest condos and townhomes, with plenty of residents who wave to one another, walk dogs, and notice new cars in driveways. It was not, to most eyes, a place where strangers could move in and out at odd hours without someone seeing or hearing something. That sense of neighborhood familiarity framed the case from the beginning: if someone came to Jodine’s home, who was it, and how did they go unnoticed?

February 14, 2007: The Final Hours

Valentine’s Day meant a check-in from Jodine’s parents. They were attentive and never controlling, and their habit of stopping by was rooted in love and reassurance rather than worry. That evening, when they arrived at Jodine’s condo, they encountered something unusual.

Inside the home, a man was present in Jodine’s bedroom. Accounts indicate the parents initially believed they had interrupted a private moment. The man conveyed—verbally or through implication—that Jodine was indisposed, such as being in the shower or otherwise occupied. Not wanting to intrude, the parents withdrew. But a gnawing sense that something was wrong led them to return shortly thereafter.

When they re-entered the home, the man was gone. They found Jodine in the bedroom, unresponsive. Attempts to revive her were futile. The room told a story of sudden violence. The 911 call triggered a rapid response by local law enforcement and paramedics, but lifesaving measures were not possible. Jodine had suffered fatal blunt-force trauma. The person her parents had briefly encountered—calm enough to speak, composed enough to leave undetected—had left behind a scene both intimate and horrific.

The Immediate Investigation

Police secured the condominium, canvassed neighbors, and began the meticulous process of reconstructing the timeline. The parents’ description of the encounter became the first vital thread. Detectives cataloged the room’s condition, signs of struggle, and any potential sexual component to the crime. They collected trace evidence from bedding, surfaces, and the entry and exit routes. They documented footwear impressions, evaluated door and window integrity, and considered whether the assailant had knowledge of the victim’s routines.

From the beginning, the case presented investigators with a paradox: it looked like a crime of opportunity yet contained hints of deliberation. The fleeting interaction with the parents suggested a suspect who could lie convincingly and depart without panic. That composure made the man memorable but also infuriatingly anonymous. Without a name, investigators leaned hard on physical evidence.

Early Theories and Lines of Inquiry

Detectives confronted a matrix of possibilities:

- Known acquaintance versus stranger: Did Jodine invite someone she knew and trusted, or was this a chance encounter with a stranger she had recently met?

- Opportunistic attack versus planned visit: Did the assailant happen upon an open door or a familiar routine, or had he targeted her specifically?

- Single-offender hypothesis: The subtlety of the intruder’s exit and the lack of reported accomplices pointed toward a single offender.

- Sexual assault motive: The crime had intimate elements, but investigators withheld particulars from the public to protect the integrity of the case.

These early theories drove targeted interviews with friends, coworkers, neighbors, and any known acquaintances. Digital traces—phone records, computer activity, and travel card transactions—were reviewed against the timeline. Nothing obvious cracked the case.

Evidence Handling and the DNA Thread

Within the first forensic sweep, detectives recovered biological material. In 2007, standard STR (short tandem repeat) profiling could generate a robust DNA profile but often relied on centralized databases that only return hits if the contributor’s DNA was already on file. The DNA developed in this case produced a unique, male profile. Initial database searches did not return a match, which implied the perpetrator had not been convicted of offenses that would require DNA submission or that his DNA had not yet entered the system.

This DNA became the golden thread—preserved, re-tested over time as methods improved, and re-queried whenever law-enforcement databases expanded or new comparison tools emerged. The case was carefully curated so that, if the day came when technology could point to a name, the biological evidence would be admissible and compelling.

The Case Goes Cold

Despite an intense early effort, tips dried up. The man seen by the parents had left almost no public trace. A reward was offered to stimulate leads. Detectives re-interviewed people, compared notes across cases in the region, and probed whether similar offenses had occurred. Years passed. The DNA profile remained the most promising path, but without a match, it was a locked door.

For the Serrin family and the Carlsbad community, the cold-case period was a long, echoing corridor—birthdays and holidays arriving with no accountability, a killer unnamed, and a grief compounded by the manner in which the crime was discovered.

A New Era in Forensics

Around the mid-2010s, forensic tools evolved rapidly. Laboratories refined low-copy DNA techniques, genealogical databases grew, and companies developed computational methods to infer biogeographic ancestry and even facial characteristics from DNA. Law enforcement agencies began to collaborate with private labs for “DNA phenotyping” and with investigative genetic genealogists who could build family trees from distant DNA relatives in consumer-facing databases (under policies that allow law-enforcement use in violent crimes).

Carlsbad investigators revisited the Serrin evidence with this toolkit. A public-facing composite and ancestry estimate were released years after the murder to solicit tips and to put a face—however probabilistic—on the unknown man. Re-engaging the public brought fresh attention to the case and, more importantly, signaled that the science had advanced enough to justify renewed hope.

Genealogical Sleuthing and the Emergence of a Name

Investigative genetic genealogy does not match a suspect directly unless that suspect’s own DNA is present in a searchable database; instead, it identifies relatives—sometimes very distant ones—whose shared DNA segments indicate common ancestors. Genealogists then triangulate those relatives’ family trees, map lines of descent, and narrow candidate lists based on age, sex, geography, and opportunity. It is labor-intensive and demands a careful blend of genetics, records research, and traditional policing.

In the Serrin case, that approach eventually converged on a man named David Mabrito. He fit the genetic inferences and the demographic window, and, crucially, there was a route to obtain his known DNA profile: he had previously provided a sample in an unrelated matter. That reference sample, compared directly against the Serrin crime-scene DNA, produced the match investigators had pursued for years.

The Suspect: David Mabrito

Publicly identified long after the crime, Mabrito was approximately the right age at the time of the homicide and had lived a transient lifestyle for part of his adult years. Accounts portray him as someone who drifted, took odd jobs, and sporadically crossed paths with law enforcement without accumulating a criminal DNA footprint that would have triggered a hit in 2007. He died in 2011, years before the match to Jodine’s case was made.

With Mabrito deceased, there would be no arrest, interrogation, or trial. Yet the forensic linkage—crime-scene DNA to his known biological profile—supplied the evidentiary closure that the case had lacked. Investigators stated confidence that he was the man in Jodine’s bedroom and the person responsible for her death.

Why the Identification Took So Long

Several factors delayed resolution:

- Database Limitations: In 2007, the suspect’s DNA simply was not in the relevant databases. A “no hit” in STR systems says little about guilt; it only indicates the profile is unknown to the database at that moment.

- Incremental Science: Methods like probabilistic genotyping, SNP-based genealogical matching, and phenotype prediction matured after 2010. Time, funding, and policy all influence when a case can be re-processed with new tools.

- Chain of Custody and Preservation: Cold cases can only benefit from future tools if the evidence is preserved impeccably. Carlsbad’s methodical handling ensured the DNA was usable a decade later.

- Human Investigation: Genealogical leads still require exhaustive records work and investigative judgment. Building and testing hypotheses across sprawling family trees takes patience and rigor.

The Parents’ Encounter: A Forensic and Behavioral Lens

One of the most striking features of the case is the parents’ brief interaction with the intruder. Behaviorally, it suggests an offender with enough social poise to speak without arousing immediate alarm. He may have banked on the parents’ embarrassment to avoid closer scrutiny. That quick calculation—offering a plausible explanation, projecting calm—bought him minutes to leave.

Forensically, the encounter narrows possibilities. It suggests the offender did not anticipate the parents’ arrival, that he was not armed in a way that compelled them, and that he valued an unobstructed exit over confrontation. The calm demeanor may indicate prior experience talking his way out of tense situations. It also implies a level of situational awareness: he knew where the door was, how to slip out, and likely had no car drawing attention outside.

Privacy, Dignity, and Responsible Storytelling

Cases that involve intimate violence demand careful language. Facts about the crime’s sexual elements, clothing, or room condition were largely withheld by investigators to protect the integrity of the case and the dignity of the victim. Public discussion benefits from that restraint. What matters most is that Jodine’s life, routines, and relationships inform how we remember her, not the spectacle of violence. Responsible storytelling centers the victim’s humanity and the family’s grief rather than lurid detail.

Community Impact and the Long Tail of Trauma

Carlsbad’s sense of safety was shaken. Residents who once left doors ajar tightened routines. Neighborhood watches revived. Informal networks of care—text chains and check-ins—intensified. The Serrin family lived with an unanswerable question for years: not only “who did this?” but “what happened in those minutes after we left the first time?” When the DNA match finally named a suspect, closure and sorrow arrived together. Closure, because a forensic truth now existed; sorrow, because a court process and sworn testimony—the rituals by which societies publicly name wrongdoing—would never occur.

What This Case Teaches About Cold-Case Work

- Time Can Be an Ally: Even when memories fade, science advances. Properly stored evidence becomes more valuable, not less, as methods improve.

- The Power of DNA Stewardship: Careful evidence handling, documentation, and the discipline to re-test when new tools emerge are the pillars of cold-case success.

- Public Engagement Matters: Reward offers, composites, and anniversary appeals keep a case in public consciousness. The right tip, at the right moment, can connect hidden dots.

- Genealogy Is a Force Multiplier: Investigative genetic genealogy, when used responsibly and within policy, can convert a dead-end DNA profile into a solvable family-tree puzzle.

Ethical Considerations Around Genetic Genealogy

The use of consumer-facing genetic databases in violent-crime investigations raises real ethical questions: consent, scope, data security, and the possibility of false leads. Best practice demands transparency about which databases allow law-enforcement access, strict case eligibility criteria (e.g., homicide and sexual assault), judicial oversight where appropriate, and rigorous confirmatory testing using law-enforcement-grade samples. In the Serrin case, the approach culminated in a direct, laboratory-to-laboratory DNA match to the named suspect—precisely the kind of high-confidence endpoint such methods are meant to achieve.

The Unanswered Questions

Even with a named suspect, certain uncertainties remain:

- Prior Contact: Did Jodine know her killer, or was the encounter brief and opportunistic?

- Approach Path: How did the offender reach and leave the condo without being seen by neighbors? Was there a preferred footpath, alley, or parking pattern?

- Offender’s History: Did the suspect commit other crimes with similar features? Are there unsolved cases elsewhere that merit cross-comparison?

- Trigger Factors: Was there a situational stressor—substance use, financial strain, a personal crisis—that made this crime more likely that night?

Such questions are common in cases resolved posthumously. They matter because they can inform broader pattern analysis and help investigators in other jurisdictions re-examine cold files with fresh hypotheses.

The Family’s Perspective

For Jodine’s loved ones, the official identification of the suspect was not an end but a moment in a long story. They had lived for years with a memory that most families will never have to carry: seeing the person who was in their daughter’s bedroom in the last hour of her life. The bravery required to speak publicly about that encounter, to maintain contact with detectives, and to endure the slow gears of science and bureaucracy, speaks to the family’s devotion to Jodine and to their community. They honored her not only by pursuing answers but also by protecting her dignity at every public step.

Law Enforcement’s Methodical Approach

The Carlsbad Police Department and partner agencies balanced three demands: rigor, patience, and communication. They guarded the case file, protected the critical facts that only the offender would know, and spoke to the public when new tools justified renewed appeals. When the genealogical analysis pointed to a likely identity, they did not rush to announce it. They sought laboratory confirmation using known reference DNA from the named individual, and only then did they present their findings, explain the method, and address questions about privacy and certainty.

Why This Case Resonates

True-crime cases often captivate because they hinge on puzzles. The Serrin case resonates for a different reason: it tests our faith in ordinary decency. Parents arrive to visit their daughter on a holiday, step into a private, confusing scene, try to show respect, and return moments later to a reality beyond imagining. The crime weapon was blunt force—personal, immediate, brutal. The offender’s outward calm contrasted with the hidden savagery inside the room. That dissonance—civility masking violence—speaks to a deep human fear, and it is why communities remember cases like this long after headlines fade.

Practical Lessons for Communities and Families

While no set of precautions can guarantee safety, the Serrin case underlines a few pragmatic points:

- Trust Instincts: If an interaction in a loved one’s home feels wrong, prioritize safety and prompt verification. Step away, call, and ask for police presence if warranted.

- Neighborhood Awareness: Familiarity with patterns—who parks where, which lights are typically on—creates the baseline needed to notice the unusual.

- Documentation: Keeping lists of frequent visitors and service providers can assist investigations if something happens.

- Victim-Centered Mindset: In public conversation, focus on the victim’s life, strengths, and community role rather than sensational details of the crime.

Aftermath and Legacy

The ultimate identification of the suspect provided an evidence-based answer but not a venue for legal closure. There would be no arraignment or sentencing, no victim-impact statement in a courtroom. Yet the forensic truth carries its own weight. It affirms that Jodine’s case mattered—to her family, to her community, and to the many professionals who refused to file it away as unsolvable. The legacy is twofold: a life remembered for warmth and perseverance, and an investigative arc that showcases the best of modern forensic persistence.

Conclusion

Jodine Elizabeth Serrin was murdered in her Carlsbad home on February 14, 2007. The investigation began with a bewildering, brief encounter between her parents and the man in her bedroom and unfolded over years into a careful, technology-assisted pursuit of the truth. DNA preserved at the scene became the lodestar that guided investigators through a decade of advances until a genealogical breakthrough, and then a direct comparison, put a name to the once-faceless intruder. Although the identified suspect died years before he could be brought to court, the case stands as a testament to patient, ethical, scientifically informed police work—and to a family’s enduring love. Jodine’s story should be remembered not only for the violence that ended her life but for the dignity with which her community and investigators sought the truth.

Discover more from City Towner

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.