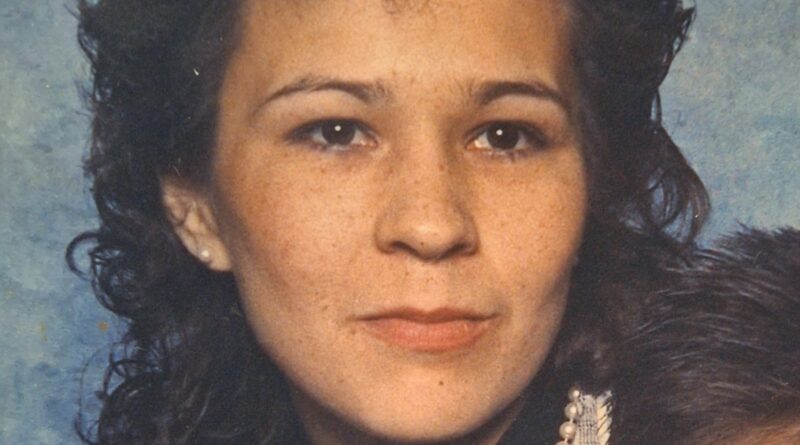

Susan Poupart Disappearance in Lac du Flambeau Wisconsin

In the spring of 1990, Susan “Suzy” Poupart was a vibrant mother of two, deeply rooted in her Lac du Flambeau community in northern Wisconsin. Known for her warm smile, generosity, and close bonds with family and friends, she attended a small house gathering on the evening of May 20th. What began as a routine night among neighbors turned into a baffling disappearance that would haunt the region for decades. When hunters discovered Suzy’s partially clothed and concealed remains on November 22, 1990, the horror of what had transpired became undeniable—and yet, many fundamental questions remained unanswered. This article delves into Suzy’s life, the events leading to her disappearance, the discovery of her body in the Chequamegon–Nicolet National Forest, and the ongoing quest for justice by her loved ones and law enforcement.

Early Life and Community Ties

Born and raised on the Lac du Flambeau reservation, Suzy was the eldest of three siblings and mother to two young children. She worked locally at a tribal social services office, where her colleagues praised her dedication to helping families in need. On weekends, Suzy often volunteered at the community center, tutoring children and assisting with elder outreach programs. Her faith—rooted in both Christian and Ojibwe traditions—guided her daily life, and she was known to begin each morning with prayer. Suzy’s children, ages two and four at the time of her disappearance, were her world; she meticulously planned for their future, saving scraps of wages to ensure they would have opportunities for education and cultural enrichment.

The Night of May 20, 1990

On the evening of May 20, 1990, Suzy attended a modest after-hours house party on Makwa Street, just blocks from her own home. The gathering was intimate—fewer than a dozen attendees, mostly friends and neighbors. Music played softly, and conversation flowed easily under the glow of a single porch light. Witnesses recall seeing Suzy laughing and chatting, enveloped in the familiar warmth of community. Around 4:00 AM, she decided to leave to return home and care for her sleeping children. Two younger men, later identified as Robert Elm and Joseph Cobb, offered Suzy a ride in a nearby Buick. No one disputed that she entered the vehicle willingly; no one reported any immediate signs of distress.

Initial Search Efforts

When Suzy failed to return home as expected, her family notified local deputies on May 22. Searches commenced almost immediately, involving tribal police, Vilas County deputies, and volunteer fire departments. Foot teams combed the wooded areas surrounding Makwa Street, while side-by-side crews scoured nearby shoreline. In the days that followed, Minnesota-based tracking K9 units joined the efforts, attempting to pick up a scent trail from the party site. Despite exhaustive grids of door-to-door inquiries and aerial flyovers, no sign of Suzy was found. As the search radius expanded to include county roads and drainage ditches, hope waned—but her loved ones remained steadfast in their determination to find her.

Six Months Later: Discovery in the Forest

On Thanksgiving Day, November 22, 1990, two deer hunters ventured deep into the Chequamegon–Nicolet National Forest, nearly twelve miles west of Lac du Flambeau. Beneath a dense canopy of spruce and cedar, one hunter’s flashlight beam caught the glint of plastic sheeting and duct tape hidden under a brush pile. Upon closer inspection, the hunters were horrified to uncover the partial remains of a woman—Suzy Poupart. Her body was partially nude, bound in places with tape, and positioned in a way that suggested an attempt to conceal rather than simply dispose. A small roadside path lay a short distance away, hinting that the perpetrator may have known the forest’s unmarked routes.

Crime Scene Observations and Forensic Findings

By the time officials responded, decomposition and wildlife activity had eroded many clues. Suzy’s skull was never recovered, complicating any effort to determine the precise cause of death. Investigators did note evidence of binding around her wrists and feet, and fragments of the duct tape bore traces of a distinctive blue adhesive pattern used in industrial packaging. Faint tire tread marks were documented near the makeshift grave site, but by then rain and snow had distorted their clarity. Clothing remnants—an undergarment and a single shoe—were catalogued, while her purse and tribal identification card lay just beyond the brush pile. No weapon was found at the scene.

Suspects and Witness Accounts

In the weeks following the discovery, detectives interviewed dozens of potential witnesses, including partygoers and community members. Elm and Cobb both submitted to questioning; each claimed they had dropped Suzy near her home after the party and drove off. Their accounts—vague on precise timing and drop-off location—failed to align completely with one another. A third person of interest, identified only as Francis “Fritz” Schuman, was later named by an anonymous tipster but never charged. Neighbors recalled hearing a vehicle engine rev loudly in the early hours of May 21 near Makwa Street, but no one reported a struggle. Family members, frustrated by the lack of physical evidence, began to suspect a deliberate cover-up or mishandled investigation.

Investigative Challenges and Cold Case Status

From the outset, the case was hampered by limited resources and jurisdictional complexities between tribal police and county sheriffs. The six-month gap between disappearance and discovery meant that critical biological evidence degraded beyond useful analysis. Early tissue samples sent to state labs yielded no definitive DNA profile, and more recent attempts to extract genetic material from preserved bindings produced only partial matches. Three John Doe judicial hearings—one in 2007 and two in the early 1990s—failed to secure compelled testimony due to witnesses invoking their Fifth Amendment rights. In absence of new leads, the investigation officially transitioned to cold case status in the mid-1990s.

Community Response and MMIP Movement

Suzy’s family refused to let her story fade into obscurity. Her daughter, Alex, only three at the time of her mother’s death, launched a GoFundMe campaign in 2024 to finance advanced DNA testing. Community members organized annual candlelight vigils at the reservation, and tribal leaders erected a prominent billboard on State Highway 47 bearing Suzy’s photograph and the words: “Justice for Susie.” Local schools incorporated her story into lessons on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Peoples (MMIP), sparking broader awareness of the crisis facing Native communities. Regional news outlets periodically revisited the case, ensuring that Suzy’s name remained in public discourse.

Advances in Forensic Technology and Renewed Investigations

In late 2024 and early 2025, investigators submitted preserved evidence—tape fragments, binding fibers, and a recovered shoe—for next-generation sequencing and forensic genealogy. Utilizing techniques pioneered by private labs, analysts hope to isolate familial DNA markers that could identify distant relatives of an unknown suspect. Additionally, high-resolution tire-tread comparison technology is being applied to archived photographs of the forest tracks. Tribal and county authorities have formed a joint task force dedicated solely to this case, meeting quarterly to review any new leads, re-interview witnesses, and incorporate tip submissions from the public.

Legacy and Continuing Search for Justice

More than three decades after Suzy Poupart vanished from her community, her two children—now adults—still carry both grief and determination. They have pursued civil suits to unseal additional law-enforcement records, pressured state legislators to allocate funding for MMIP investigations, and lobbied for improved jurisdictional collaboration between tribal and non-tribal agencies. Suzy’s story has become emblematic of larger systemic issues: resource scarcity in rural law enforcement, historical distrust between Native communities and investigators, and the persistent invisibility suffered by Indigenous victims. Each November 22nd, her memory compels renewed action, reminding all who learn of her case that unresolved loss demands resolution, and that justice delayed can still be justice achieved.

Discover more from City Towner

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.