Kentucky Fried Chicken Murders in Kilgore Texas

In the early 1980s, Kilgore, Texas, was a community defined by its boom‑and‑bust oil heritage. Located along U.S. Highway 259 in Gregg County, the town’s economy revolved around nearby oilfields, and its modest downtown strip bustled with diners, cafés, and fast‑food restaurants catering to roughneck workers and families alike. Against this backdrop of economic uncertainty and tight‑knit social bonds, the local Kentucky Fried Chicken on the highway’s edge was more than a mere fast‑food outlet—it served as a gathering place, a late‑night refuge, and a familiar landmark for the townspeople.

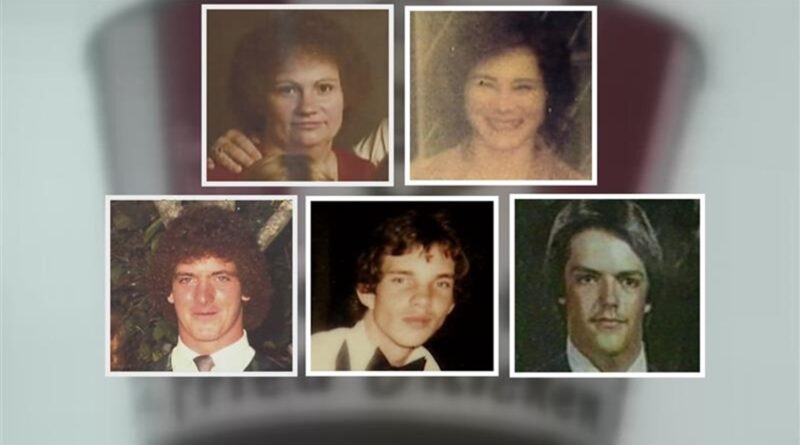

The Victims and the Final Closing Shift

Late on the evening of September 23, 1983, five individuals remained inside the KFC after closing time: three young employees—Opie Ann Hughes, Joey Johnson, and Monty Landers—and two patrons who had lingered over greasy buckets of chicken—local resident David Maxwell and visitor Mary Tyler. As the clock ticked past 10 p.m., the crew finished cleaning duties and prepared to lock the doors. Their laughter and routine chatter masked the approach of armed intruders who would turn that ordinary close‑up into one of Texas’s most chilling unsolved homicides.

The Abduction in Broad Daylight of Night

Shortly after the restaurant’s “closed” sign flicked on, witnesses later recounted seeing three masked men force entry through the back door, brandishing handguns and moving with clinical efficiency. The intruders ordered everyone to raise their hands, shouting blurred threats over the hum of the ventilation fan. Within moments, the five hostages were ushered into a waiting vehicle—one employee momentarily resisted and was struck with the butt of a pistol. No screams pierced the night beyond the hired‑hand buildings, and the perpetrators drove off along Highway 259, leaving behind empty grease buckets and overturned mop buckets as silent witnesses.

Discovery of the Crime Scene

The following morning, a passing resident unearthed a bloodied mop and scattered chicken bones in the KFC’s parking lot. Inside, chairs were overturned, drawers rifled, and streaks of blood stained the tile floor. Concerned neighbors, alerted by unanswered phone calls and flickering neon signs, alerted law enforcement. Deputies from Gregg County secured the building, found a single spent shell casing in the kitchen area, and noted the absence of all five who had closed the restaurant. The discovery ignited a massive manhunt involving local officers and Texas Rangers, but no bodies were yet found and no suspects were in custody.

The Bodies in the Oil‑Field Roadside

Hours later, hunters stumbled upon the bodies of the five missing victims in a field off County Road 232—a narrow, unpaved stretch winding through scrub brush toward an abandoned pumpjack. Each victim lay face down, execution‑style, with single gunshot wounds to the back of the head or torso. One woman bore evidence of sexual assault. Investigators estimated that all five had been killed within minutes of reaching the field, their final moments a brutal end to what should have been an uneventful closing shift.

Early Investigation and Missteps

In the wake of the discovery, law enforcement combed the scene for forensic evidence. They lifted fingerprints from a discarded cigarette butt, collected shell casings, and recovered a torn fingernail. An early suspect, local drifter James Earl Mankins Jr., was arrested when his DNA briefly appeared to match the fingernail scrapings. However, flawed testing and contaminated samples led to his release when the match could not be confirmed. Public confidence wavered as weeks became months with no arrests, and the case gradually receded from media headlines—yet lingered in private nightmares of the community.

The Case Grows Cold

By the late 1980s, the KFC murders had grown as cold as the oil rigs lying idle at dawn. Investigators maintained a rotating duty officer to watch for breakthrough leads, and crime‑scene photos and evidence sat in secured lockers. Local detectives revisited witness statements, while Texas Rangers reopened files, but jurisdictional friction and limited forensic capabilities of the era hampered progress. As key personnel retired or transferred, institutional memory faded. Families of the victims clung to hope, but each year’s anniversary brought fresh despair rather than answers.

Forensic Breakthrough Two Decades Later

Advances in DNA technology by the early 2000s offered new promise. FBI and state labs honed techniques to extract genetic material from minute or degraded samples. In 2005, decades‑old fingernail clippings, a blood‑stained napkin, and fabric fragments were reexamined using polymerase chain reaction amplification. Investigators matched one DNA profile to Romeo Pinkerton—a convicted offender already incarcerated for unrelated charges—and a second profile to his cousin, Darnell Hartsfield. A third profile, from semen evidence on one victim’s clothing, did not match either man, suggesting an accomplice still at large.

Arrests of Romeo Pinkerton and Darnell Hartsfield

In November 2005, Pinkerton and Hartsfield were formally charged with five counts of capital murder. Romeo Pinkerton, who had a lengthy criminal history dating to the late 1970s, surprised many by pleading guilty in October 2007. He received five concurrent life sentences. Hartsfield, then in his 40s and also incarcerated for prior offenses, opted for trial. In September 2008, a Gregg County jury convicted him on all counts, resulting in five consecutive life terms without the possibility of parole.

Trial Testimony and Defense Strategies

During Hartsfield’s trial, prosecutors painted a portrait of premeditation and familial conspiracy: the cousins met earlier that evening to discuss robbery targets, surveilled the KFC, and executed their plan with ruthless coordination. Pinkerton’s guilty plea agreement spared him detailed cross‑examination, but he provided enough cooperation to bolster the prosecution’s timeline. Hartsfield’s attorney argued for diminished responsibility and questioned the integrity of decades‑old evidence storage, but jurors found the DNA link compelling despite defense claims of contamination and police misconduct.

The Unanswered Question of the Third Suspect

Even after convictions, the mystery of the third assailant endures. The unmatched DNA sample—indicative of sexual assault on one victim—has resisted identification through standard databases. Law enforcement agencies have periodically sought familial genetic genealogy leads, but concerns over legal admissibility and finite evidence have slowed efforts. For the families, every DNA genealogy headline rekindles both hope and frustration: could the missing perpetrator finally face justice, or will this final link remain elusive?

Impact on Victims’ Families and the Community

The loss of five young lives left an indelible scar on Kilgore. Memorial services held in the local civic center drew hundreds of mourners, and annual vigils by community volunteers underscored the case’s lasting resonance. The KFC site was eventually demolished and replaced by a vacant lot marked only by a small plaque. Survivors’ children, now adults, have campaigned for expanded cold‑case resources and legislative reforms to allow more aggressive use of genetic genealogy in violent‑crime investigations.

Legal and Legislative Legacy

The KFC murders helped spur changes in Texas’s cold‑case protocols. In 2009, the state legislature allocated funds for DNA backlog reduction, and in 2014, Texas became one of the first states to formalize guidelines for investigative genetic genealogy in law enforcement. Advocates cite Kilgore as a cautionary tale of forensic stagnation, emphasizing the human costs of years lost to bureaucratic inertia.

Final Reflections on a Dark Chapter

Forty years after that closing shift in 1983, the Kentucky Fried Chicken murders remain a stark reminder of both human cruelty and the slow arc of justice. Thanks to DNA science, two men answered for their crimes, yet the community still awaits closure on unanswered questions. In Kilgore, the memory of Opie, Joey, Monty, David, and Mary persists not merely as victims, but as catalysts for transformation—in policing practices, forensic innovation, and collective resolve to never forget.

Discover more from City Towner

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.