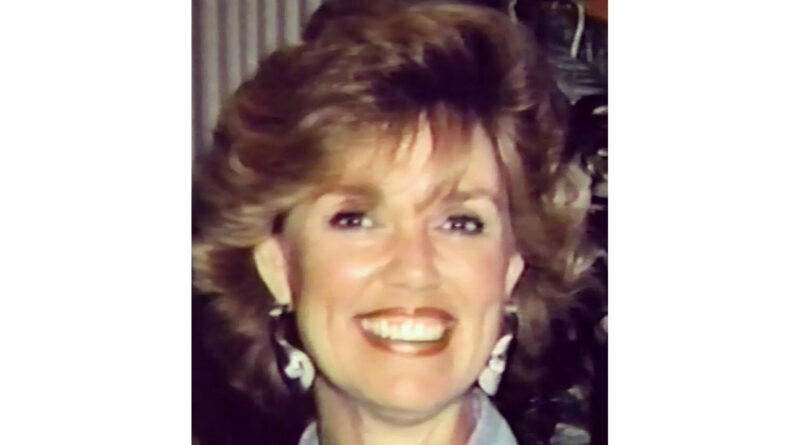

Patsy Wright NyQuil Laced Poisoning Death in Arlington Texas

On the early morning of October 23, 1987, a well-known Arlington, Texas, businesswoman named Patricia “Patsy” Wright collapsed and died in her own bedroom under circumstances that would baffle investigators for decades to come. Initially presumed to be a tragic accident or sudden illness, Patsy’s death was later revealed to have been the result of a calculated poisoning. The lethal agent—strychnine—was discovered in her nighttime cold medicine, NyQuil, transforming what should have been a routine quiet evening into one of the most mystifying unsolved homicides in Tarrant County’s history.

Early Life and Career

Patsy Joan Smith was born on November 12, 1943, in Narrows, Virginia. She exhibited an early affinity for both business and the arts, eventually marrying William Jay Wright and relocating to Texas. Together, Patsy and her husband built two thriving wax museum attractions in the Dallas–Fort Worth area: the Wax Museum of the Southwest in Grand Prairie and the Wax Museum at Love Field. Known for their unique lifelike figures and elaborate historical dioramas, these museums cemented Patsy’s reputation as a savvy entrepreneur with a flair for entertainment and tourism.

After William Wright’s untimely death in 1977, Patsy took sole control of the businesses. She remarried briefly but ultimately became known as a fiercely independent woman who juggled her role as a single mother, community volunteer, and museum owner. Friends and employees described her as warm, generous, and meticulous—traits that would later underscore the cruelty of her killer, who had to understand her nightly routine to strike undetected.

The Night of October 23, 1987

On October 22, Patsy Wright spent the evening hosting a small gathering of close friends at her Arlington home. As was her custom, she prepared a light late-night snack—a few crackers and a cup of warm tea—then retired to her upstairs bedroom just after 11:00 p.m. According to those guests, Patsy was in good spirits, joking about a minor cold that had left her congested. She mentioned taking NyQuil, an over-the-counter nighttime cold remedy to help her rest. No one noticed anything unusual as they departed around midnight, and Patsy was left alone in her quiet, alarm-equipped home.

Discovery and Emergency Response

At approximately 3:00 a.m. the following morning, Patsy’s sister Sally Wright received a distressed phone call. Patsy’s words were slurred: she complained of violent nausea, difficulty breathing, and severe muscle spasms. Suddenly, the line went dead. Sally alerted her husband, Steve Horning, and the two rushed to Patsy’s house. The front door was locked, but windows near Patsy’s bedroom were left open. After climbing through a window, Steve found his sister-in-law convulsing on her bed. Paramedics were summoned and began CPR, but Patsy never regained consciousness.

Autopsy and Poisoning Revelation

Doctors initially suspected cardiac arrest or an adverse reaction to cold medication. Patsy’s body was taken for autopsy at Arlington’s county morgue. Eight days later, toxicology reports stunned investigators: Patsy’s bloodstream contained a fatal concentration of strychnine, a powerful neurotoxin historically used as rodenticide. Even more chilling, trace amounts of strychnine were found in her half-empty bottle of nighttime cold medicine. Strychnine disrupts motor neuron signals, causing convulsions, respiratory failure, and excruciating pain—none of which matched the mild cold symptoms Patsy had described to her friends.

Investigation and Suspects

Arlington Police quickly ruled Patsy’s death a homicide. Their first priority was identifying anyone with both access to pure strychnine and intimate knowledge of Patsy’s habits. They interviewed family members, business associates, employees, and close friends. Key persons of interest included:

- Steve Horning, Patsy’s brother-in-law, who had practiced mouth-to-mouth on Patsy and thus risked exposure. He inherited her shares in the wax museums.

- Robert Cox, Patsy’s second ex-husband, with whom she had ongoing legal disputes over property and financial settlements.

- Lori Ann Williams, Patsy’s former secretary who had died under mysterious circumstances in 1984.

- Leo Fikes, a former boyfriend and chemist who had the means to obtain strychnine.

- Stanley Lester Poynor, a drifter seen near Patsy’s museum on the night of its subsequent arson.

Although many volunteered for or were subjected to polygraph tests, none produced definitive evidence. No witnesses recalled suspicious purchases of strychnine, and forensic lab records showed that pure, regulated-grade strychnine—not the impure rat-poison formulations—had been used.

The Strange Clues

Several perplexing details emerged during the probe. Two used dinner plates were discovered on a tray near Patsy’s bed, suggesting an intimate late-night visitor rather than a secret poisoning agent. The home’s security system had been disarmed—unusual for Patsy, who prided herself on maintaining strict safety measures. Investigators found no forced entry, implying the killer was known and trusted. Additionally, Patsy had recently changed her life insurance policies, naming new beneficiaries, which some speculated provided financial motive.

Related Unsolved Incidents

In the years surrounding Patsy’s death, two other baffling events occurred. In 1984, her secretary Lori Ann Williams died unexpectedly, with the cause undetermined; some believe strychnine may also have been involved. In 1988, the Wax Museum of the Southwest was destroyed by arson in what appeared to be an insurance-motivated blaze. A man named Poynor was shot by police during his attempted escape from the scene, leaving investigators without the chance to question him. None of these occurrences have ever been definitively linked, but many armchair detectives and private investigators view them as interconnected chapters in a larger, still-unsolved saga.

Impact on the Community

Patsy Wright’s shocking death reverberated through Arlington and the broader DFW metroplex. Local news outlets ran continuous coverage in late 1987, and community fundraising efforts helped Patsy’s children cope with their mother’s sudden loss. The wax museums, temporarily closed after her passing, eventually reopened under new management but never fully regained the public’s trust. For decades, “What happened to Patsy Wright?” became a refrain among true-crime aficionados, inspiring podcasts, amateur sleuth blogs, and late-night cable TV specials.

Legacy of the Case

Despite advances in forensic science—DNA genealogy, digital records, and modern toxicology—Patsy Wright’s murder remains officially unsolved. In 2017, Arlington Police briefly reopened the investigation to apply new genetic genealogy techniques to evidence collected in 1987, but no viable matches emerged. Cold-case investigators still review tips periodically, and Crime Stoppers of Tarrant County continues to offer rewards for information leading to an arrest. The wax museums, long shuttered or rebranded, stand as silent witnesses to a crime that left more questions than answers.

Conclusion

More than three decades after that fateful October night, Patsy Wright’s death endures as one of Texas’s most haunting cold cases. A woman of community standing, entrepreneurial spirit, and close family bonds was felled not by chance but by a deliberate act of lethal cunning. The strychnine-laced cold medicine, the disarmed home alarm, and the intimate knowledge required to execute such a crime all point to a killer who remains at large. In remembering Patsy Wright, Arlington honors her memory and renews the hope that one day the truth—long buried in mystery—will finally come to light.

Discover more from City Towner

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.