Tara Leigh Calico Disappeared on Morning Bike Ride in Belen New Mexico

On September 20, 1988, nineteen-year-old Tara Leigh Calico set out from her family’s home in Belen, New Mexico, for a bike ride she knew by heart. She was a meticulous planner—classes, studying, exercise, and time with friends all slotted into a tidy daily rhythm—and the morning ride along New Mexico State Highway 47 was as much a ritual as it was training. She intended to be back by midday to keep an afternoon commitment. The sun was cooperative, the air dry, and the road familiar. Tara rolled away on her bicycle with a portable cassette player and the unspoken confidence that comes from routine.

The distance she usually covered—roughly a 36-mile out-and-back—was not casual. She was fit, fast, and alert. She wore bright colors and traveled a route that threaded south along Highway 47, a two-lane corridor hemmed by scrub, fencelines, and occasional homes and businesses. In a landscape where sightlines are long and traffic can be sparse, cyclists are both visible and exposed. Tara knew the schedule of passing cars and the location of the turnoffs. She knew which stretches felt comforting and which felt lonely. She also knew when to be home: around noon. When noon came and went, Tara did not return.

A Schedule Broken

Tara’s punctuality was a kind of family constant, a reliable beat everyone knew to listen for. When she missed that beat, concern hardened quickly into alarm. Her mother expected to see Tara moving through the doorway, sweat-flushed and hungry, reaching for water and routine. What instead arrived was silence, and then the slow press of time. A check of the route began—in a car rather than on foot—tracing the path she would have taken out of town and along Highway 47.

On that drive, pieces of Tara’s world began to appear. Fragments from a personal stereo were found along the shoulder, as if dropped deliberately or scattered in panic. Cassettes that should have been inside the player were on the ground. The bike—bright, distinctive—was nowhere. The roadway itself offered little else: no skid marks tied to a collision, no toppled fence, no obvious sign of a fall. It was as if the rider had been lifted from the road while the road remained unchanged.

The Call to Police and the First Hours

The Colfax-like clarity of the family’s alarm sharpened into official action. Local law enforcement and county authorities were notified, officers moved to canvas the route, and the first round of interviews began with anyone who might have been driving Highway 47 that morning. Those first hours in a disappearance are decisive: choices about where to search, how widely to alert, and which facts to publicize can enlarge or constrict the funnel of information.

In Tara’s case, investigators confronted a paradox of place. The route afforded broad visibility; drivers could see far ahead, and a cyclist could be tracked in a rearview mirror for a long time. But that same openness meant a vehicle could stop, pull off, or pace a rider without drawing immediate challenge. If someone had orchestrated a roadside approach, the road’s scattered residences and stretches of open land could have hidden an interaction from casual witnesses. The clock, as it does in so many missing-person cases, began to work against clarity.

The Known Route and the Unknown Event

State Highway 47 was not a mystery to Tara. The ride south from Belen went past landmarks she knew and mile markers she could recite. She habitually left around 9:30 a.m. and, depending on wind and traffic, would be on the return leg before noon. She often carried a cassette player for company—a normal detail that became pivotal once pieces of that player were located.

Those fragments mattered for two reasons. First, they suggested a struggle or an intentional attempt to leave a trail. Second, they anchored the investigation to a specific stretch of roadway at a specific window of time. That window—between the late morning and noon—would be where investigators concentrated witness statements. People remembered a young woman on a bike. People remembered vehicles behind or near her. But memory in the wild fades at the edges; colors blur, makes and models dissolve, and certainty evaporates under the heat of a formal interview.

Witness Glimpses and Vehicle Leads

From the first canvass, reports trickled in about vehicles that seemed to shadow or pass close to Tara along the route. Some motorists characterized what they saw as normal highway proximity; others described driving behavior that felt too attentive to be accidental. A few accounts mentioned a pickup truck; others thought they saw a car pacing from behind. None of those sightings resolved into an incontrovertible plate number or an identity. This is a painful structural feature of roadside abductions, if that is what occurred: the encounter can be fast, the vantage points poor, and the details too ordinary to command attention until it is too late.

The lack of a recovered bicycle was its own kind of witness. In a collision, metal bears witness: bent frames, scarred paint, gouges in the roadway. In a voluntary disappearance, a bike is abandoned in haste. In an abduction, a bike can be lifted into a vehicle as efficiently as a person. That absence—no bicycle—stood in opposition to any theory of a crash or a runaway. It supported what the family suspected almost immediately: Tara did not simply fail to return; she was prevented from returning.

The Family’s Parallel Investigation

Families in missing-person cases become researchers by necessity. Tara’s family posted flyers, spoke to news outlets, traded information with neighbors, and retraced the route more times than memory can count. They learned the cadence of investigative follow-ups, how long it takes to process a tip, and how easily a rumor can masquerade as a lead. They also confronted a steady erosion of patience from the broader world: after the first burst of attention, a community’s alarm can yield to other concerns, while the family remains stuck in the one story they cannot put down.

Even as law enforcement held briefings and expanded lists of persons of interest, the family assembled a parallel archive: maps, notes from conversations, and timelines built to the minute. Absence is hard to document; it forces you to study what is not there. Where did the bike not appear? Which cameras did not exist in 1988 that might have marked her passing today? Which drivers did not realize they were witnesses until the news taught them the significance of 11:45 a.m. on Highway 47?

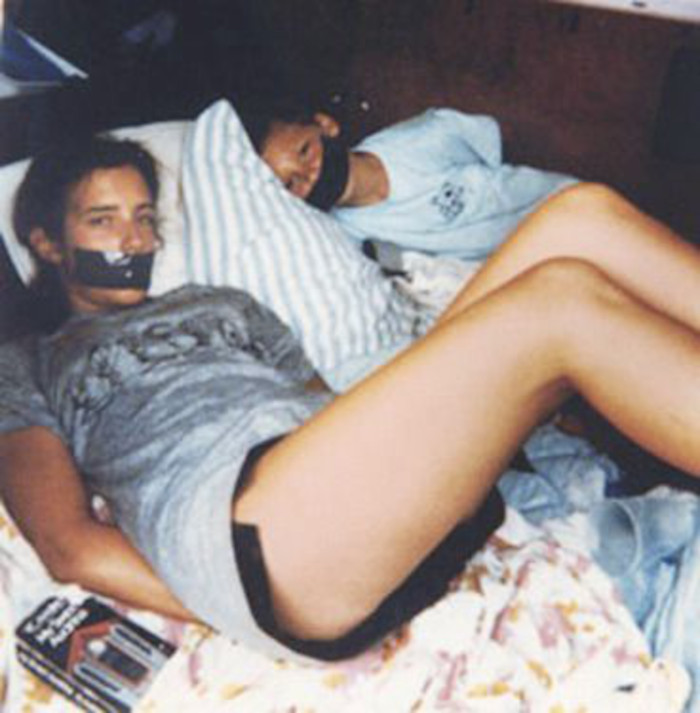

The Polaroid That Transfixed a Nation

Nine months after Tara vanished, a strange and terrible image surfaced in Port St. Joe, Florida: a Polaroid photograph showing a young woman and a young boy bound and gagged in the back of what appeared to be a vehicle. The photo’s brutal staging and the faint domesticity of its setting—pillows, a paperback book—created a scene that people could not stop reading for clues. The picture spread across national news broadcasts and newspapers. Families with missing daughters and missing sons were called into a fresh season of hope and fear.

Tara’s family was among those asked to look. The young woman in the Polaroid bore a resemblance to Tara: similar features, similar age, similar coloring. The boy resembled a New Mexico child who had also disappeared the year before. Analysts examined the film stock and determined it was manufactured after Tara’s disappearance, ruling out a hoax made from older materials. Outside experts compared facial features and scar placements. Different labs reached different conclusions; one assessment leaned toward a match for Tara, another away from it, and federal analysis ultimately could not confirm the identity of the young woman in the image. In time, the boy in the photograph would be separated from the New Mexico case by new findings, and the Polaroid—once an electrifying possibility—receded into the case’s periphery: unresolved, suggestive, unproved.

Building a Case Without a Scene

Criminal cases are built on scenes, and scenes are built from the stubborn residues people and machines leave behind. The ache at the center of Tara’s case is the minimalism of the material record. The stereo fragments gave the route a center point; tire patterns in the dirt shoulder could be argued over; and witness statements could be layered to triangulate time. But the scene—as a bounded set of evidence that points in one direction—never cohered. No bike. No recovered clothing. No forensic anchor strong enough to resist the drift of decades.

In the absence of hard physical evidence, investigators looked to patterns. They surveyed similar roadside incidents, questioned offenders with histories that might encompass opportunistic abduction, and consulted with agencies beyond the county line. Leads rose and fell. Suspicions formed, then stalled. The case entered the long half-life that so many cold cases occupy: neither closed nor actively breaking, sustained by periodic review and the unspent attention of those who refuse to let it fade.

The Human Scale of Loss

To read the record is to risk missing the human scale. Tara was not a symbol; she was a person with classes to attend, friends to meet, inside jokes to carry forward. She had a mother who once rode the same route with her and later decided not to—an everyday decision that a grieving mind can torture into tragic significance. She had plans for the afternoon she never reached, plans that remained in calendars and on notes stuck to the fridge. That specificity is the cost of disappearance: a family inherits not just the fact of loss but the inventory of what the lost one would have done next.

Anniversaries multiply in the lives of the missing: days of disappearance; birthdays; holidays; the day a Polaroid appeared; the day a rumor took hold and then collapsed. For families, each anniversary is part memorial, part re-petition of the call for information. The public may hear that call as a reminder; families hear it as oxygen.

Media, Memory, and the Weight of Attention

The media’s relationship to unsolved disappearances is complicated. Stories like Tara’s can draw national attention, but attention is mobile and moves toward novelty. The first time a case is profiled on television, the phone lines flood. The fifth time, the audience shifts. Long-form reporting can humanize a victim and enlarge a case’s possibility space by generating new tips. It can also re-ignite speculation that burns energy investigators must then spend chasing stale smoke.

In Tara’s case, each substantial national profile brought calls, letters, and off-ramps: people who were certain they saw her far from New Mexico, people who were certain they knew a man who said too much in a bar, people who were certain the Polaroid was proof. Investigators triaged, followed, recorded, and archived. Tips that looked promising on television sometimes failed at the threshold of verification; tips that seemed marginal sometimes unlocked a small corroboration in a witness statement. The rhythm of hope and narrowing is its own kind of stress test on a community.

Technology and the Passage of Time

When Tara disappeared in 1988, consumer DNA databases did not exist, license-plate readers were not lining highways, and rural roads did not hum with dashcams. Today’s cold-case work leans on exactly those tools: re-testing minute traces with more sensitive methods; mapping historic cell-site coverage; leveraging genealogical research to explore offender identity in cases where crime-scene DNA exists. Where such evidence is absent, technology still offers support: improved records search, enhanced image analysis, and the quiet work of cross-referencing old notes with new databases.

Time can be enemy and ally. Memories fade, witnesses move, and records are lost. But people also age into willingness to talk, loyalties shift, and conscience ripens. A case that felt closed by fear in 1988 can feel newly open to a different witness in 2023. The paradox of cold-case work is that the door can open again at any moment if there is someone on the other side of it ready to turn the knob.

Theories, Restraint, and Responsible Curiosity

Any unsolved case invites theories, and Tara’s disappearance has generated many. Some emphasize opportunism: a passing motorist who recognized vulnerability and acted. Others suggest premeditation: someone who knew the route and the timetable. Still others map to the Polaroid, positing a network or an abductor capable of transporting victims across state lines. Responsible curiosity in such cases demands restraint. Theories must be held against the discipline of what is known: the timeline, the objects found, the absence of the bicycle, and the geography of Highway 47. To move beyond those anchors is to risk turning a person’s life into a story that serves our appetite for closure rather than the imperative of truth.

The Community’s Long Vigil

Belen is not a metropolis that easily forgets its people. Over the decades, Tara’s name has been kept present in local consciousness by family, friends, classmates, teachers, and neighbors. Candlelight vigils and memorial runs, case profiles in regional media, and informal conversations in shops and kitchens all function as a sustained civic vow: she is not forgotten here. In New Mexico, the landscape itself participates in memory; long roads and long horizons teach patience, and patience is what a case like this requires.

The vigil is not passive. It is an insistence on possibility—that someone, somewhere, knows something specific about a particular morning in September 1988 and that telling it matters. Communities keep cases alive by protecting the space in which such testimony can finally be offered and believed.

What We Know, What We Don’t, and What We Can Do

What we know is simple and devastating. Tara left home in Belen for a morning ride along State Highway 47. She did not return. Pieces of her personal stereo were found along the shoulder, consistent with a struggle or an attempt to mark the route. No bicycle was recovered. Witnesses saw a cyclist and vehicles; none of those sightings matured into a chargeable identification. Months later, a disturbing Polaroid from Florida stirred national attention but has never been conclusively connected to Tara’s case. Investigators have pursued leads across years, with periods of renewed activity and public statements of progress, but without a public resolution.

What we do not know is the fulcrum of the case: who encountered Tara that morning and how that encounter became an abduction. We do not know where the bicycle went or where the critical objects—if any—were taken after the road ceased to speak. We do not know whether the person or persons responsible were local or passing through, whether they were known to Tara or unknown, whether an opportunity was seized or an intent was executed.

What we can do—what anyone can do, even after decades—is to preserve accuracy when we speak about the case, resist the urge to embellish, and make space for tips that meet the threshold of specific, verifiable detail. The smallest remembered fragment can be useful: a plate partially recalled, a decal on a camper shell, a driver’s habit of traveling Highway 47 on late September mornings, a conversation that seemed unimportant until the calendar gave it meaning. Cases sometimes turn on memories that finally find the right ears.

Enduring Hope

Hope in a long-unsolved disappearance is not a naïve denial of time; it is a discipline. It is choosing, again and again, to believe that truth exists and can be found. For Tara’s family, hope is active: it is advocacy, participation in renewed investigative efforts, and the unglamorous work of making sure her name remains audible in the chorus of unresolved cases. For investigators and community members, hope is the willingness to look one more time, ask one more question, and test one more rumor against the hard edges of fact.

Tara Leigh Calico’s story is, above all, the story of a particular person on a particular road at a particular hour. Fixing our attention on that specificity keeps us from turning her into a symbol detached from the reality of her life. She was a daughter, a student, a friend, and a cyclist who loved the morning road. She should have come home. That she did not is an open question with a human name attached—one that deserves an answer measured not in speculation but in evidence.

Discover more from City Towner

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.