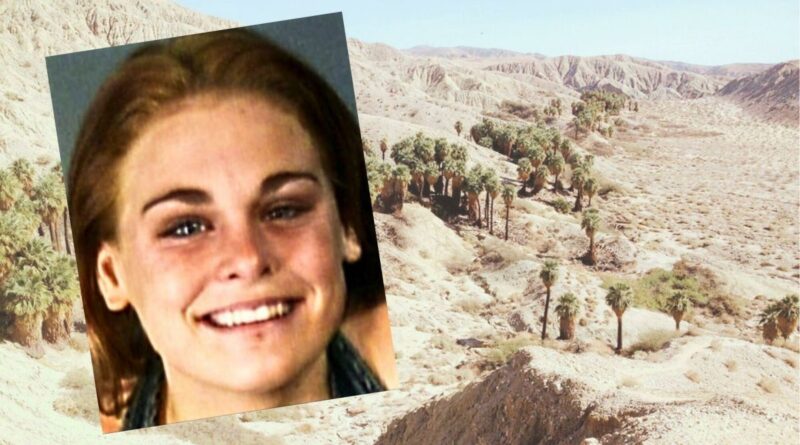

Christina Ann Battin Goes Missing in Riverside County California

On June 8, 2003, a teenager named Christina Ann Battin disappeared in Riverside County, California. It was the kind of warm early summer day when plans are simple and hours feel generous, yet by night a family began to sense that something had gone wrong. Friends expected calls that never came, relatives made rounds of phone checks, and the first reports were filed with local authorities. In the days that followed, the ordinary facts of a young person’s life were gathered into a case file, and a community learned how quickly a life can slip from view when a timeline breaks and no one sees where the line goes.

The person behind the missing poster

Christina was 14 years old in June 2003. She was around 5 feet 6 inches tall, with blue eyes and hair that family and friends say could appear brown or strawberry blonde depending on dye and sunlight. At school and with friends she carried the usual mix of humor, mood, and energy that marks the early teen years. Adults who knew her describe a girl who could be shy with strangers and open with people she trusted, who liked music, movies, and late conversations about small plans that feel as large as the horizon when you are young. The portrait matters because it anchors public attention in a real person, not a case number, and because habits and personality inform what investigators consider likely when a teen goes missing.

The setting and its split picture

Riverside County sprawls across desert flats, foothill neighborhoods, and corridors of motels, gas stations, and shopping strips. It is a county of cars, of short hops and long drives, of places where teens meet before going somewhere else. In the record of Christina’s final day there is a small but persistent ambiguity, one side pointing to Thousand Palms and another to Hemet. Both are within the county, both have the mix of residential blocks and commercial strips that allow a young person to move between familiar spots. That split in the paperwork has never been the center of the case, but it does color every attempt to reconstruct the last hours. The difference between two cities can be the difference between sets of cameras, groups of friends, and the chance encounters that shape an evening.

The last confirmed day

What can be stated clearly is this. June 8, 2003, is the date of last contact. Christina was seen in Riverside County that day. She did not make the next expected call, and she did not appear at the next expected place. When families and friends realized that silence was replacing routine, they started the checks that form the backbone of any first response. Calls to friends who might have seen her. Stops at locations where she might have gone. The early hours in any missing teen case are a race between hope that she will answer and the practical need to act as if she might not.

The first report and the first searches

Once the report went in, deputies and detectives began the steps that bring order to a small storm of information. They took statements, noted times that could be anchored, and recorded descriptions of clothing and any bag she might have had. They traced the last known movements as best as the record allowed. When a young person is known to have a wide circle, that circle becomes the map. Investigators ask about rides that were planned, about meetups that might have been suggested in passing, about references to parties or out of town friends. They look for camera coverage at gas stations and restaurants and stores near the last known places. The question that drives every early step is simple and relentless. Who saw her last, where did they see her, and how certain are they.

The lead that many people remember

One narrative thread has held attention for years. After the day of last contact, a friend reported seeing Christina leave a motel with an unidentified young man. The vehicle described in that account was a blue sport utility vehicle, and the man was said to be in his early twenties with a visible tattoo on his left arm. The detail repeats because it offers the kind of image that sticks in the public mind, a pair of figures stepping from a door, a color and make of vehicle that you can imagine. Investigators handle such accounts with care. They look for the motel registry, for footage that might confirm the moment, for anyone on staff who recalls names or patterns. They ask whether the description matches any person already on their radar. They accept the possibility that memory fuses nights together and that a confident witness can be wrong.

Why the case proved difficult from the start

Teens often move without broadcasting their plans. They get rides that were not arranged the day before and meet people who are friends of friends. That fluidity complicates timelines. If the last place is not a home or a well lit store, camera coverage can be spotty. If the last voices were on a prepaid phone, account data may be thin. If a teen’s social circle spans multiple towns, the number of people to talk to grows quickly, and each person adds names and places. Investigators triage. They look for the nexus, the person in the web who touches the most threads. They look for contradictions between versions of the day. They build a timeline that may be precise in one hour and blurred in the next.

The vehicle, the man, and the limits of description

Descriptions like blue sport utility vehicle and early twenties male with a tattoo are useful and also common. A county the size of Riverside can hold thousands of vehicles that fit that phrase, and tattoos are less a distinguishing mark than they once were. Investigators look for the specific within the general. A model year. An aftermarket wheel. A pattern on the arm that could be matched to a known person if someone recognizes it. They circulate quiet questions to people who would have reason to know the man, not wide posters that would spook him. If the motel lead is correct, then there was a moment with other potential witnesses. A clerk. A maintenance worker. Another guest. Every one of those people can sharpen or dull the picture.

The two city discrepancy and how to treat it

Thousand Palms and Hemet appear in retellings of the case, a fact that can frustrate readers who want neat lines. There are reasonable explanations for the split. One is bureaucratic. Reports sometimes carry the residence city while posters list the city of last contact. Another is practical. A teen may live in one city and be seen in another on a given day. The best way to handle the discrepancy in public summaries is to acknowledge it and keep focus on the county and on the known movement patterns of Christina’s social circle. People who knew her do not remember case numbers. They remember where she liked to spend time, which stores she visited, and which friends gave rides most often.

Family, community, and the long work of attention

Families learn to carry hope and to manage the daily tasks that do not wait. They also become the most constant partners for investigators. They provide photos that show different hair colors and styles across months. They list friends who drifted in and out of the circle. They take calls that a detective might not receive because a classmate is more likely to answer a cousin than a uniform. Communities can help by sharing correct details rather than rumors, by marking anniversaries with renewed calls for information, and by remembering that a missing teen grows into an adult who might still be out there waiting for someone to recognize a face.

What could still move the case forward

Cold cases can turn on small hinges. A single image discovered on an old hard drive. A saved receipt with a time stamp that eliminates or confirms a theory. A text recovered from a backup. A person who stayed silent in 2003 because they were afraid of being blamed for a ride given, who now understands that withholding information has done more harm than good. Technology has advanced. Items collected that once seemed unhelpful can sometimes yield meaning under modern analysis. Digital forensics can wring context from devices and accounts that were once opaque. Even if the physical trail is limited, a renewed set of interviews can surface contradictions that did not register years ago.

Reasoned possibilities and how to weigh them

In the absence of a confirmed last sighting with video or a recovered personal item, the set of possibilities remains broad but not infinite. One possibility is that Christina left willingly with someone she knew and was then harmed or prevented from returning. Another is that she left with someone she barely knew and was quickly moved out of familiar spaces. A third is that an accidental event occurred and people who were present panicked and failed to seek help. Each scenario can be tested against what is known of her habits, of the reporting of the motel moment, and of the behavior of people in her circle in the days after she vanished. Sudden changes in stories, rapid departures from the area, or the quiet deletion of accounts are the kinds of signals investigators look for.

The importance of precise public memory

Effective public engagement depends on clarity. The date is June 8, 2003. The county is Riverside. Christina was 14, about 5 feet 6 inches tall, with blue eyes and hair that could appear brown or strawberry blonde. A commonly discussed lead places her leaving a motel with an unidentified young man and entering a blue sport utility vehicle. Those are the bones of the case that should be repeated, and repeated cleanly, so that anyone who recognizes a piece can bring forward information that matches what matters most.

Closing reflection

A teen’s life is a mosaic of small places and quick choices. On June 8, 2003, somewhere in Riverside County, the pieces around Christina shifted in a way that left an empty space where a person should be. The people who loved her have filled the space with effort and patience, and the people who investigate have carried forward lines that still hold the possibility of resolution. Cases like this are not solved by rumor. They are solved by one good voice or one preserved fragment that lines up with what careful work already suggests. Until that voice is heard or that fragment is found, the county that holds both Thousand Palms and Hemet will share the same obligation. Keep the name present, keep the details straight, and keep the door open for the person who finally decides to tell what they know.

Discover more from City Towner

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.