The Ocoee Massacre Over 50 African Americans Lost Their Lives on Election Day in Ocoee Florida

The Ocoee Massacre on November 2, 1920, remains one of the most violent and tragic episodes of racial violence in American history. Taking place on Election Day in Ocoee, Florida, this event saw a mob of white residents launch a deadly assault on the town’s African-American community, resulting in widespread destruction, deaths, and forced evacuations. Today, the massacre is remembered as both a chilling example of racial oppression and a vital moment in the fight for civil rights and social justice.

Tensions Build: The Political and Social Climate of 1920

By the early 20th century, Ocoee was a small but prosperous community in Orange County, Florida, with a significant population of African-American residents who had established their own homes, businesses, and farms. According to the 1920 census, Ocoee’s 255 African-American residents lived alongside 560 white residents, and many Black citizens had acquired land and economic independence in this predominantly white region. Despite the challenges of the Jim Crow South, they had built a thriving community, purchasing farmland and becoming active participants in the local economy.

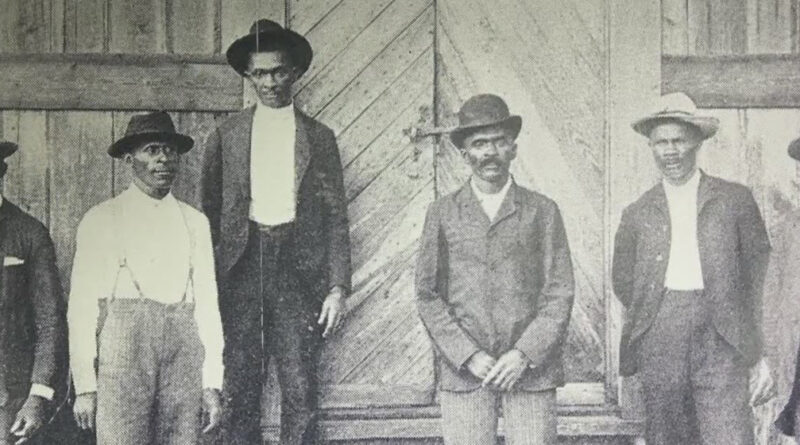

However, the promise of prosperity and equality was overshadowed by growing tensions as the 1920 presidential election approached. Across Florida, African Americans were organizing and registering to vote, encouraged by prominent Black leaders and allies like Judge John Moses Cheney, a white lawyer and U.S. Senate candidate who openly supported Black suffrage. Among the leaders in Ocoee’s Black community were Mose Norman and July Perry, prosperous landowners who paid poll taxes for Black residents unable to afford it, helping them to register to vote. This movement posed a direct threat to the status quo, and white supremacists, including the Ku Klux Klan, mobilized to ensure Black citizens would not exercise their voting rights.

Election Day Erupts in Violence

On Election Day, November 2, 1920, Mose Norman arrived at the polls in Ocoee to vote. Despite his registration, poll workers denied him entry, demanding that he pay the poll tax again. When Norman refused, tensions escalated. Reports differ, but some accounts suggest that Norman returned later with a shotgun and attempted to assert his right to vote. After facing continued resistance, he retreated but remained determined to hold his ground.

Word of Norman’s confrontation spread quickly, and soon a white mob gathered in response. Local authorities, including Deputy Clyde Pounds of the Orange County Sheriff’s Office, deputized white residents to “arrest” Norman and his friend July Perry, claiming they were instigating violence. The mob, numbering over 100 men, converged on Perry’s home, where they believed Norman was hiding. As they demanded that Perry and Norman surrender, Perry attempted to defend his family and property. A violent exchange ensued, resulting in the deaths of two white men. Perry, injured in the altercation, was eventually captured and taken into custody.

The mob’s wrath was far from satisfied. While Perry lay gravely wounded in jail, he was abducted by the mob, dragged to a light post near Judge Cheney’s home in Orlando, and lynched as a brutal warning to other Black residents who dared to vote. This act of violence signaled the beginning of a coordinated assault on Ocoee’s Black community.

Destruction of the African-American Community in Ocoee

The violence that followed was swift, brutal, and devastating. Reinforced by white paramilitary groups from nearby towns, the mob swept through Ocoee’s Black neighborhoods, burning homes, churches, schools, and other structures to the ground. Entire families were forced to flee as their homes and livelihoods were destroyed. Many sought refuge in nearby orange groves, swamps, and surrounding towns like Winter Garden and Apopka, where larger Black communities lived.

Reports estimate that between 30 and 80 Black residents of Ocoee were killed, while hundreds more fled, leaving behind all they had worked for. Within hours, Ocoee’s Black community had been eradicated, with many properties seized by white residents. The 1930 census recorded just two Black residents remaining in Ocoee, marking the town’s transformation into an all-white “sundown town” — a place where Black people were threatened or forbidden from living.

The Aftermath and the Silence that Followed

Following the massacre, local newspapers downplayed or entirely ignored the violence, with few accurate reports of the scale of devastation and death toll. The town’s Black population had been forcibly driven out, and those who managed to escape were left with nothing. Many families, like those of Mose Norman and July Perry, lost not only their loved ones but also the land and businesses they had built over years. Properties left behind were often sold at a fraction of their value or seized outright, resulting in significant financial losses for Black families who had invested heavily in Ocoee.

The silence around the Ocoee Massacre persisted for generations. Public records were minimal, and many local residents grew up unaware of the events. Even descendants of survivors often remained in the dark, as their families chose not to speak of the horrors they had witnessed. Pamela Schwartz, chief curator at the Orange County Regional History Center, noted that most Ocoee residents had no knowledge of the massacre, as it had been systematically erased from the town’s collective memory.

Survivors’ Stories and the Legacy of Silence

Gladys Franks Bell, daughter of survivor Richard Allen Franks, recalls her father’s harrowing escape that night, carrying his younger brother through the swamps to safety. Her father, despite enduring unimaginable trauma, rejected hatred and embraced forgiveness, a legacy Bell captured in her book, Visions Through My Father’s Eyes. Stories like Bell’s bring the history of Ocoee into sharper focus, revealing the resilience of survivors and the haunting silence that followed.

For decades, the events were suppressed, with newspapers minimizing the deaths and referring to the massacre in vague or misleading terms. Efforts to silence the memory of the massacre extended to threats against those who tried to speak openly about it, and for nearly 80 years, any remembrance or acknowledgment of the event remained hidden.

Recognition and Reconciliation: Honoring the Victims

Efforts to recognize and remember the Ocoee Massacre have increased in recent years, fueled by the dedication of historians, community activists, and descendants of survivors. The work of historians like Walter White of the NAACP, who investigated the massacre shortly after it happened, helped piece together the truth despite the initial suppression of records. His findings, along with local historians’ research, exposed the horrifying extent of the violence and the systemic efforts to erase the massacre from public memory.

In 2020, a century after the massacre, the Florida state government took a significant step toward reconciliation by mandating that the events of November 2, 1920, be included in the state’s educational curriculum. Governor Ron DeSantis designated November 2 as “Ocoee Massacre Remembrance Day,” and sections of State Road 438 were renamed “July Perry Highway” in honor of one of the massacre’s most prominent victims. These actions, while long overdue, reflect a growing commitment to acknowledging the historical injustices endured by Ocoee’s Black community.

The Orange County Regional History Center has also played a vital role in educating the public, opening a landmark exhibition titled “Yesterday, This Was Home: The Ocoee Massacre of 1920.” The exhibition features testimony from descendants, historical documents, and digital archives, all dedicated to preserving the legacy of those who lost their lives and livelihoods.

Resilience in the Face of Injustice

For the families impacted by the massacre, the struggle for justice and remembrance has been a multigenerational journey. Figures like Allen Franks, who chose love over hatred, exemplify the spirit of resilience. His daughter, Gladys, continues to advocate for awareness and healing, hoping that her father’s example can inspire others to transcend bitterness.

The Ocoee massacre is now acknowledged as a painful but essential chapter of American history, illustrating the power of truth-telling as a means of healing.

Legacy and Lessons from the Ocoee Massacre

The legacy of the Ocoee Massacre resonates beyond the history books, reminding us of the painful reality of racial violence and the long road to justice and healing. This tragedy underscores the need to confront the past, not only to honor those who suffered but also to educate future generations about the ongoing fight for civil rights and equality.

The massacre stands as a testament to the courage of individuals like Mose Norman and July Perry, who sought to exercise their right to vote even in the face of profound danger. Their actions, along with the sacrifices of countless others, serve as a powerful reminder that the struggle for justice is never without cost. As Ocoee and the wider community work to remember and reconcile with this dark chapter, the memory of those lost continues to inspire efforts to build a more inclusive and equitable society.

Discover more from City Towner

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.